Digital interactive map showcases public art on U-M’s campus

On a warm summer afternoon, Adi Behar, a junior in the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design, sat contemplating the Rampant Unicorn statue outside the Michigan League.

As an intern at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the research she was compiling about the artwork would become the foundation for a new interactive map that connects users to the 110 works of public art scattered across campus.

Spearheaded by UMMA curator Jennifer Carty and Erika Larson, manager of the university’s Art in Public Spaces initiative, the map launched in July as a digital interactive tool for users to engage with U-M’s vast public art collection.

“Everybody loves to spin Tony Rosenthal’s the Cube when they pass the Regents Plaza or to run through Maya Lin’s Wave Field on North Campus,” Carty said, adding that rendering the collection in a digital format “allows for this rich accessibility of the public art collection that didn’t exist before.”

The map is part of a larger push within UMMA to create a digital database of public art, a process the team hopes will make viewing U-M’s widespread collection of public art more accessible. This project launched after a $5 million commitment from the President’s Office for public art was announced in January.

“This database is the first step to really establishing a core place where people can go to start exploring public art on campus,” Larson said.

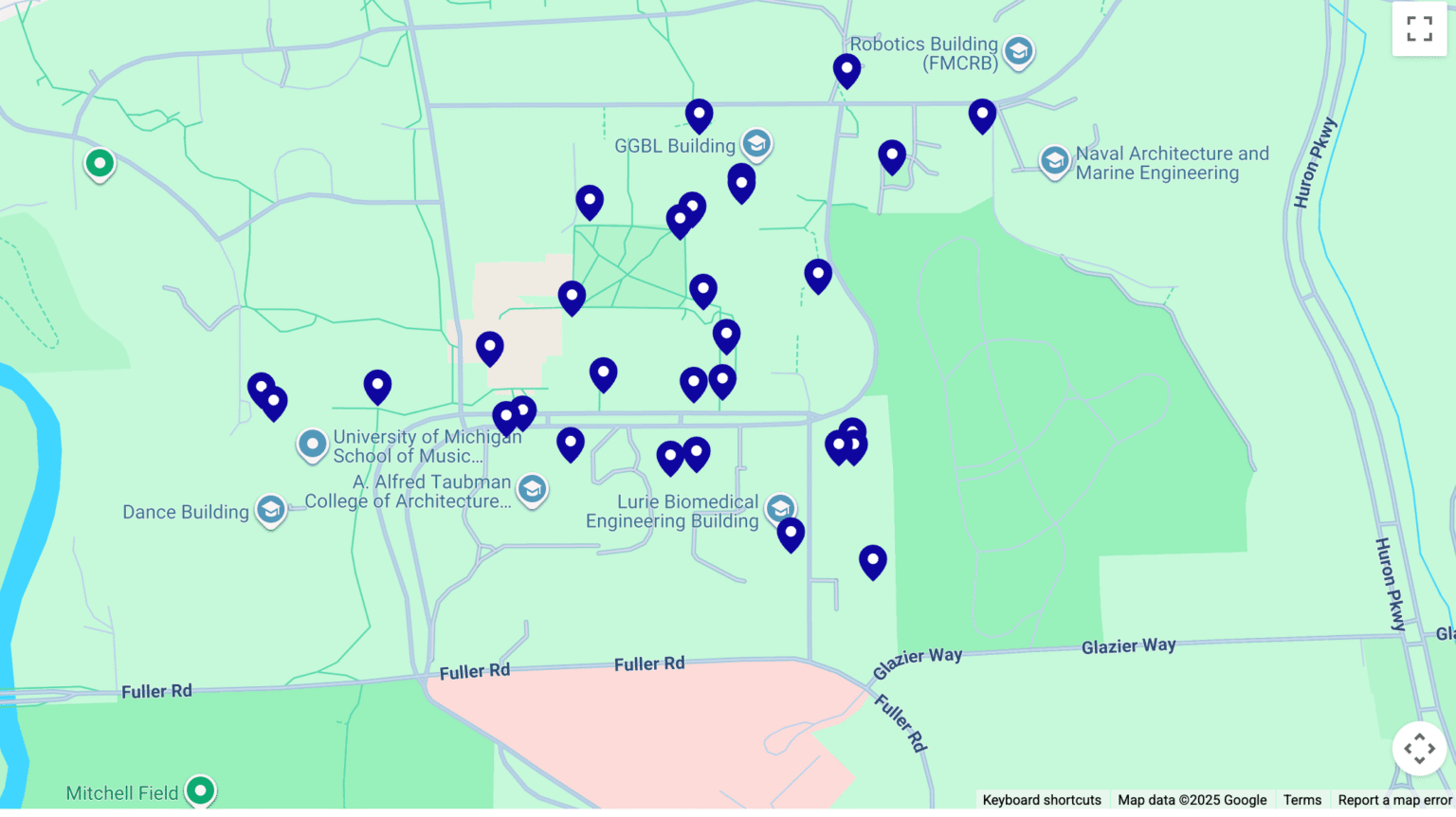

A screenshot of the U-M Museum of Art’s interactive map.

To start, the map was nothing more than a list of works on a sheet of paper. Behar and one other student intern, Yuchen Wu, took on the task of finding the story behind each of the university’s works of public art. They combed through old newspapers, emails and other files to fill in the gaps, creating digital records for each and every work of public art that included latitude and longitude location data.

“It was really fun,” Behar said. “It felt like a scavenger hunt.”

Carty, who became U-M’s first curator of Art in Public Spaces in 2023, made the map one of her initial priorities.

“Coming into this role I really wanted to build a public art collection that is about our place and about the stories here on campus and that speak to our student and faculty needs,” Carty said.

“You would be surprised how many people reached out to us to tell us that there was no place to find the public art collection,” Larson said.

In addition to its role as a digital discovery and exploration tool, the map underscores U-M’s extensive history of public art displays. Many of the works on the map have been fixtures on campus for decades, becoming quiet landmarks that persist even as the university evolves.

“Coming back to campus as an alum in this new role I have seen how different buildings have changed and how campus continues to grow,” Carty said. “But you see public artworks endure.”

For the UMMA team, public art is important because of its inherent accessibility. Behar noted that in museums, “there’s some sort of barrier between person and art, not just monetary but physical because you can’t go that close.There’s always some sort of barrier guideline. With public art you can get really close and observe it and look at it from all angles.”

While museum staff are constantly coming up with more ways to get people in their doors, public art confronts campus visitors every day.

“Public art is available to everyone and it’s something that whether or not people want to encounter it, they’re going to,” Larson said, adding that Ann Arbor is an ideal place for public art to live. “Ann Arbor is a place where people are very open-minded and willing to be challenged by art, so we can do more exciting things.”

The public can expect to see new works of art in the coming years.

“It feels like we’re perfectly poised to take on these next five years and show some really extraordinary public artworks and activations on campus,” Carty said.